I started my business, Norm’s Computer Services, because I loved doing what I do, and I knew people would benefit from my services. The problem was: I had no idea how much they’d be willing to pay for them.

For your business to be sustainable, you’ll need a pricing strategy that generates adequate income for you while also being attractive to clients and customers. I spent a lot of time making sure my pricing strategy worked, and it’s sustained me for nearly five years. Here’s how I’d recommend creating your pricing strategy so you can hit the ground running.

The pricing page on my website

What is a pricing strategy?

A pricing strategy is a plan for setting the best price for your products or services. The goal is to set a price that will entice customers to buy, but that isn’t so low that you’re not making a profit.

Sure, you could just trial-and-error a bunch of prices until you find the price that maximizes profit without deterring potential customers—and there will probably still be some of that even after you choose a pricing strategy for your business. But you’ll spend a lot less time and money starting with a pricing analysis than you will taking a complete shot in the dark.

Factors to consider when pricing a product

You likely know off the bat that you’ll need to consider your own business costs and competitor prices so that you can find a price that earns a profit but isn’t so high that it drives potential customers to other businesses with better deals. But unfortunately, it’s not that simple: there are a lot of factors you’ll need to consider in order to determine the best pricing strategy for you.

Cost

I know I just said cost wasn’t the only factor to consider, but it is the most important one to start with. If your prices aren’t higher than your costs, you’ll be out of business before you even get your company off the ground.

When calculating costs, make sure you include:

-

Product materials

-

Employee wages (that includes what you pay yourself!)

-

Overhead costs (rent, insurance, utilities, taxes, etc.)

-

Software and services for things like accounting, marketing, and legal

-

Shipping and transportation

Economic factors

When costs change, your prices will have to change in order to stay competitive and keep making a profit. Businesses that rely directly on commodities as supplies—so things like lumber, oil, and metals—will be most vulnerable to economic fluctuations, but all industries are affected in some way or another by global, political, and social changes.

Figure out what economic conditions are good for your business and what events could affect your supply and demand. Learn what to keep an eye on in the news so that you can plan ahead for spiked supply costs or dips in demand. Businesses in volatile industries will need to build a survival cushion into their profit margins to make sure they have enough funds to stay in business during slow periods.

Competitor pricing

I clearly remember something my then-CEO asked me when I was in the early stages of planning the launch of my own business. He said, “What’s your point of difference?” In other words, in a crowded marketplace, how are you going to stand out?

Your prices don’t always need to be lower than your competitors’, but if they are higher, you need to be able to justify it with added quality. Your products don’t always need to be quality, but if they’re low-quality, you’ll need to be able to justify it with lower prices. Where you fall on either side of this trade-off determines your value position, which we’ll discuss in a bit. But no matter how you decide to position your product, you’ll need to stay up-to-date on what your competitors charge, pricing trends in your industry, and what pricing models work best for your market.

It’s usually not difficult to find out what your competitors charge—either by visiting their websites or by calling them to ask. As you gather this information, keep a spreadsheet where you can record prices and note things like introductory offers, loyalty programs, and discounts.

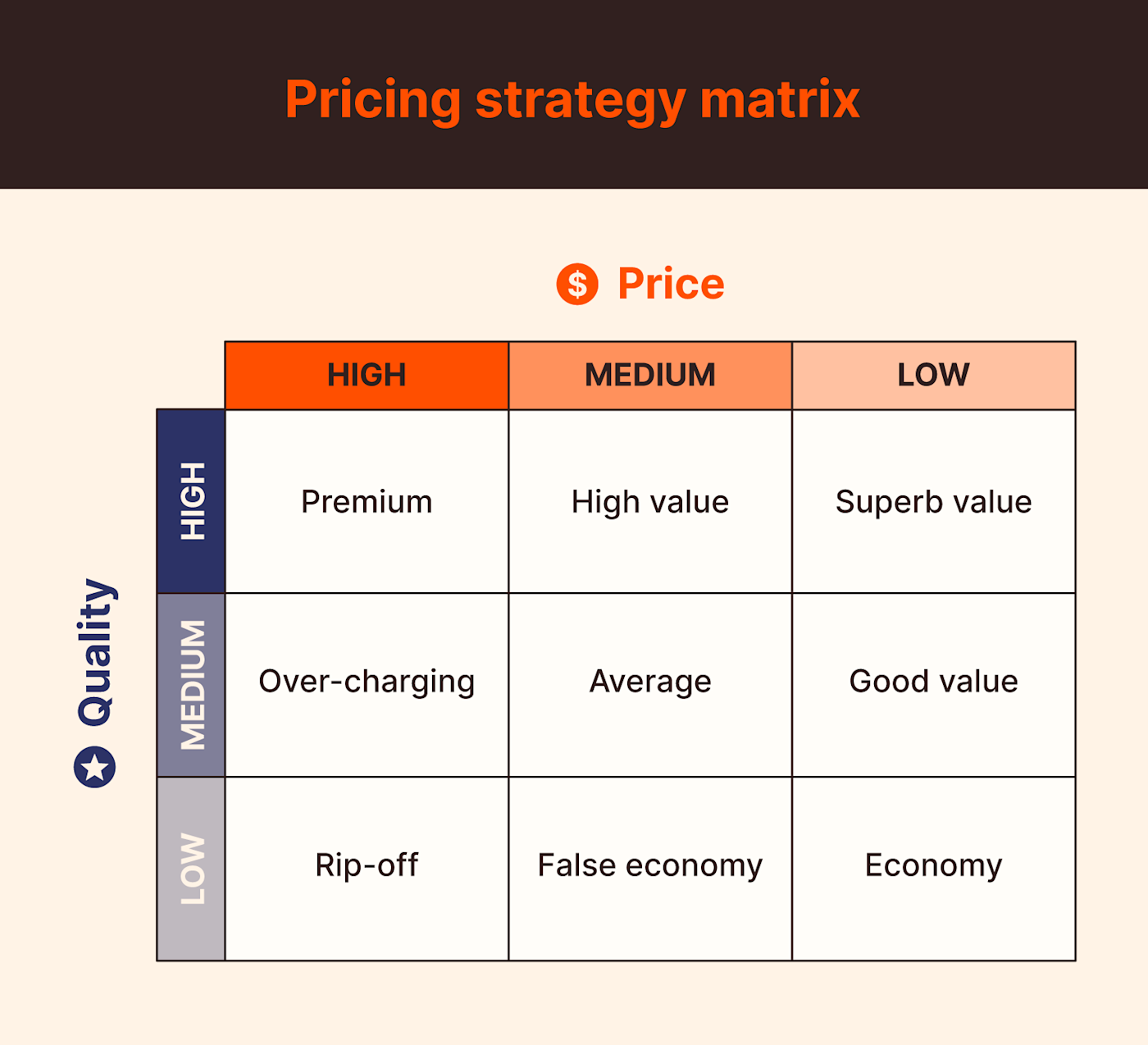

Positioning

It’s a common misconception that businesses have to sell good-quality products to be successful. There are buyers at every price and quality level; what matters is how your product quality and price are positioned with respect to each other.

One of the easiest industries for demonstrating this concept is the airline industry, because there’s no way to mistake the difference between a high- and low-quality purchase when there’s a literal curtain dividing them. Normally, price and quality will align with one another. First-class tickets offer high quality at a high price, economy tickets offer low quality at a low price, and everyone else gets piled into coach.

Value prices occur when quality is higher than price—when you fly during off-peak times or get upgraded to first class for free. When demand is high and seats are limited, the airlines can afford to charge higher prices for lower-quality seats, counting on the fact that you’ll pay full price for a terrible seat if it’s your only option.

When you apply this to your own pricing, ask yourself what kind of value your product or service offers. Are you solving an urgent problem, or is your product more for comfort and enjoyment? If you sell a first-class product, you’ll lose money by selling it at economy prices. If you sell an economy product, you’ll need to sell it for a bargain price.

7 common pricing methods

Your core pricing strategy has to do with what you’re selling: a luxury, a bargain, or just a good product for a good price. Once you have that figured out, you’ll move on to choosing a pricing method, which is the how of your pricing strategy.

Pricing methods are sort of like plays in a playbook. Your product is probably not going to switch from being a luxury to a bargain and back again, but you can (and, in some cases, should) switch up the pricing method you’re using to better meet your market demands.

Here, we’ll look at seven of the most common pricing methods, plus how and when to use them.

Value-based pricing

The first pricing method is probably the one you’re most familiar with: value-based pricing. You might think of it as the “default” pricing method, since it consists of finding what the customer is willing to pay (the WTP price), making sure it’s higher than the cost of production, and setting your price somewhere in between.

If the business needs to raise prices for whatever reason, it can do so as long as the new price is still within the WTP range. If it’s not, the business has to find a way to increase that range—usually by adding value that will increase the amount the customer is willing to spend in exchange.

Cost-plus pricing

A very similar method to value-based pricing is cost-plus pricing. Instead of basing prices on what the customer is willing to pay, businesses set prices by determining the cost of production and their ideal profit margin. For example, if a product costs $100 to make and a company’s target margin is 15%, then the product will sell for $115.

Cost-plus prices still need to fall within the WTP range, but they’re not chosen based specifically on what the customer is willing to pay. If the cost-plus price falls outside the WTP range, the company either needs to adjust its target margin or find a way to lower production costs.

Competitive pricing

Another very recognizable pricing method is the competitive pricing model, in which a business sets prices based on what competitors are charging for comparable products. If your product offers something your competitors don’t, you don’t always need to set prices competitively. But if you’re selling a bargain product, you need to be able to beat the competition.

When I formulated my own pricing model, I decided that I would want to be considered competitive, but not cheap. That meant that my pricing was on par with my peers but that I avoided the use of any terminology such as “budget,” “cheap,” or “cheapest” in my marketing.

One of the things I tried early on was to offer the first 15 minutes of work free of charge. This meant that if I solved the issue within that first quarter of an hour, the job would have been completely free—but I don’t recall any occasion when this actually happened.

In fact, clients told me they’d want to pay even if I had solved the issue in under 15 minutes, because they didn’t feel good about paying nothing for a service that involved someone coming to their home. It was an attractive offer that increased my competitive edge without impacting my bottom line.

Economy pricing

Similar to competitive pricing, economy pricing involves setting the lowest prices among your competitors to attract bargain buyers. But unlike competitive pricing, economy pricing specifically targets people who will consciously sacrifice quality in exchange for a cheaper price. Knowing this, you can source cheaper supplies, eliminate extra features, and make other changes to lower your production costs so that you can offer extremely low prices while continuing to make a profit.

The fast fashion industry is infamous for its reliance on economy pricing. Clothes are created quickly using cheap (and often ethically questionable) labor, and they wear out quickly. This allows stores to sell highly trend-conscious clothing, since customers need to replace their clothes more frequently. Unfortunately, it also causes major environmental damage—and usually doesn’t even save customers money compared to buying more expensive but longer-lasting clothing.

Penetration pricing

As a new business, you may find that you need to set your prices toward the lower end of the spectrum. Penetration pricing is when a business sets the price of a product or service low at the beginning, then raises the price once the company is more established.

Businesses that provide a service can draw customers in with low pricing, then win their loyalty with great service. Introductory offers can be a great way to entice new clients or customers. For example, you could offer a fixed price or percentage off the first job, or a portion of free labor. At least one of my competitors offers a 10% reduction on the labor charge for returning customers. In my view, a better approach to customer retention is to offer them that 10% off the first job—and then do such good work for them that they won’t mind being charged the full price for subsequent jobs.

Dynamic pricing

Have you ever pulled out your phone intending to grab a rideshare on a busy weekend night or (I wince just thinking about it) a holiday? Those jaw-dropping price surges are the result of what’s called dynamic pricing, or pricing that changes fluidly according to availability and demand.

Truly dynamic pricing requires an algorithm that can automatically adjust prices according to purchasing activity. Uber’s CEO isn’t sitting behind a Wizard of Oz curtain declaring price surges; the app automatically increases prices when demand is higher than the number of drivers on the road. A less immediate version of dynamic pricing can be seen at the gas pump, where prices change frequently in response to demand but aren’t automatic (in some states, like New Jersey, they can’t change more than once per day).

For small businesses, dynamic pricing works best with services or custom products that require a price quote, since customers expect prices to be different depending on the project and circumstances. If your prices are listed on your site and you change them constantly, you’ll drive away potential customers who perceive you as unpredictable or unreliable.

Price skimming

Price skimming is the opposite of penetration pricing, where you start by setting the maximum price and gradually lower it over time. This strategy works best with products that have major releases, like laptops or cars. By price skimming, you’ll be able to capture early buyers willing to pay top dollar for the latest and greatest; then, as you gradually lower the price, you’ll be able to sell the maximum number of products at each price before dropping it again.

One of the most well-known price skimmers is Apple, which has made its product launches into full events with tickets and fans to build as much hype as humanly possible. Mega-fans buy the newly unveiled products the moment they’re available, even waiting in lines overnight outside Apple Stores to do so. As each new product is released, the older models get shunted down the pricing ladder to capture buyers with lower WTP points.

As you start off in business, it’s important to remember that you can change your pricing strategy as you go along. This is a marathon, not a sprint, so it’s more about building a client base of satisfied customers who will come back to you again and again than it is to make as much money as possible as quickly as possible.

And the good news is that you don’t have to get everything right from the very beginning. You can try different approaches and make adjustments as you go until you’re achieving the outcomes you want. Eventually, you’ll settle into a groove that works for you.

This article was originally published in December 2020 and has since been updated.

[adsanity_group align=’alignnone’ num_ads=1 num_columns=1 group_ids=’15192′]

Need Any Technology Assistance? Call Pursho @ 0731-6725516